Antonio Ray Harvey | California Black Media

The disturbing story of Los Angeles County’s Bruce’s Beach Park — location of the first West Coast seaside resort for Black beachgoers and a residential enclave for a few African American families – has been making headlines around the country.

One hundred years ago, Manhattan Beach city officials seized the Bruce’s beachfront property from an African American couple, Charles and Willa Bruce, citing an “urgent need” to build a city park. But the area was not developed for recreational use after it was forcefully taken from the Black owners.

In addition to the Bruce’s land, the city grabbed about two dozen other properties from African American families along the city’s Pacific shore using eminent domain laws.

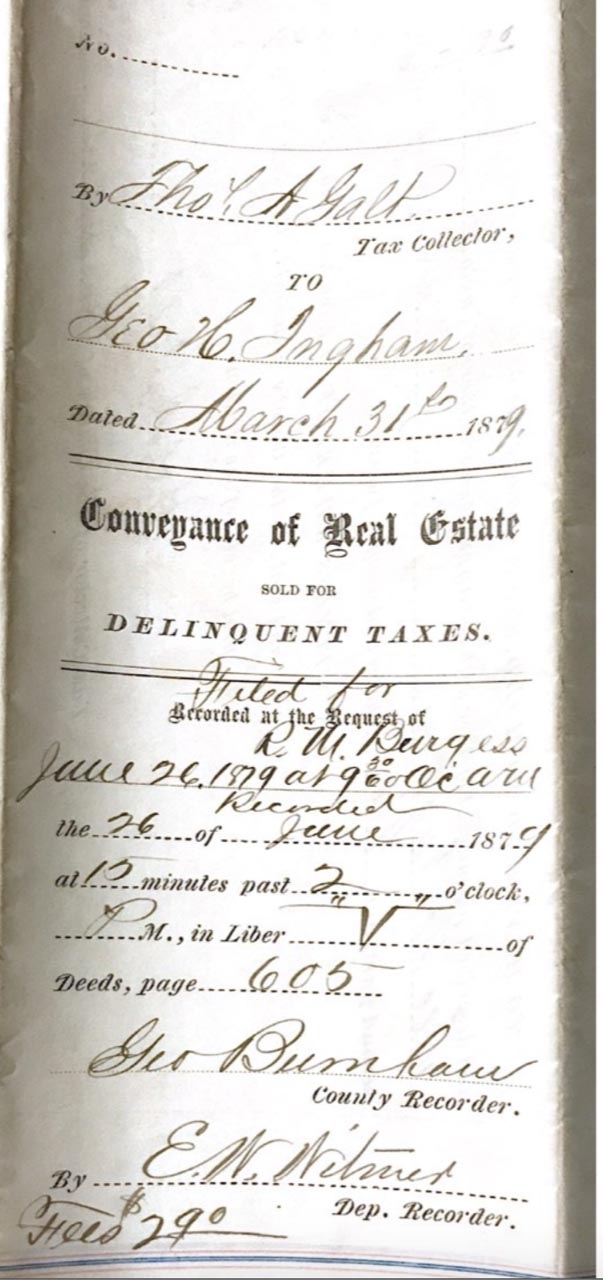

“This was a strategy and a tactic used everywhere – here in California. That’s why we get so much resistance when we fight it,” said Sacramento resident Jonathan Burgess, referring to Bruce’s beach and other properties he said were forcefully and illegally taken away from Black Californians in the past. Burgess’s family is engaged in a fight of their own to reclaim property in Northern California’s Gold Country that he says authorities stole from his ancestors.

Gold country is a mineral-rich area along the foothills of the Sierra Nevada that was a popular destination during California’s 19th century Gold Rush.

“The timing couldn’t be better because of what’s happening in Manhattan Beach. First, you have to reconcile the wrongs before you talk about reparations. That’s how you repair everything that happened afterward. You have to ask and wonder why there’s not massive wealth passed down from California’s early African American pioneers,” Burgess continued.

Like Burgess, descendants of other Californians whose ancestors’ properties were unlawfully seized or stolen, are beginning to speak up. They are demanding restitution for their losses. With the backing of some lawmakers, advocates and historians, these incidents involving direct land theft, intimidation, coercion, and more, will likely become cases to investigate as California begins to wrestle with its history of slavery and discrimination and how those forces have impacted African Americans throughout the history of the state – and still contribute to racial inequity today.

Last year, Gov. Gavin Newsom signed Assembly Bill (AB) 3121 into law. Former Assemblymember and current California Secretary of State Shirley Weber authored the landmark law which mandates the creation of a committee to study Californians involvement in slavery and discrimination and make recommendations for how African Americans can be compensated for injustices sanctioned or committed by government.

On April 9, Los Angeles County Supervisor Janice Hahn announced that the county will return a plot of Manhattan Beach land to the family of the Black couple who purchased Bruce’s Beach in 1912 for $1,225.

But last week the City Council of Manhattan Beach, a mostly-White city in southern Los Angeles County, voted to issue a statement of acknowledgement and condemnation,” stopping short of voting to apologize to the Bruce’s descendants.

There is also support in the California Legislature. Sen. Steven Bradford (D-Gardena) has announced new legislation, Senate Bill (SB) 796. It would exempt the Bruce’s Beach property from state zoning and development restrictions and enable the county to return the site to its rightful owners. The legislation is co-authored by Sen. Ben Allen (D-Santa Monica) and Assemblymember Al Muratsuchi (D-Torrance).

After the Bruces bought the ocean-view parcel of land, which was considered a remote area at the time, they began operating Bruce’s Lodge and managed to construct a boarding space, an entertainment facility, café, and tents for changing clothing along with bathing suits for rent. Attracting African American beachgoers, the business incensed White neighbors who began buying property around the beach or posting No Trespassing signs near the front entrance of the beach, forcing guests to walk nearly two miles to get to and from the resort. There was also an arson attack on the resort reportedly committed by local members of Ku Klux Klan.

In Tulare County, the historic African American farming town of Allensworth suffered a similar fate to Bruce’s Beach. It was the first municipality in California to be founded, financed and governed by Blacks with its own schools, library, church, hotels and businesses.

Founded by Allen Allensworth, a man who born into slavery in Louisville, Kentucky in 1842, and later became a Colonel in the U.S. Army and the highest-ranking Black officer when he retired in 1906, the town had as many as 300 residents during its peak in the 1920s. But by 1925, a company called the Pacific Farming Company that was responsible for supplying irrigation water to the town, did not.

The lack of water affected the townspeople livelihood and the farmers’ productivity in the Central California town, and a lengthy and expensive legal dispute ensued between Allensworth and the company, which depleted all of the town’s resources. The residents and nearby farmers soon abandoned their land and slowly left the area in search of employment elsewhere.

Then, there’s the city of Folsom, 20 miles east of Sacramento. Parts of that city sits on land purchased by Joseph Libbey Folsom from the estate of William Leidesdorff, a wealthy African American merchant from San Francisco.

Leidesdorff obtained and owned the property from a Mexican land grant called “Rancho Rio de Los Americanos,” which was initially the city’s name before it was changed to Folsom. When Leidesdorff, 38, passed away in 1848 of Typhoid fever, his estate was passed on to his mother Anna Marie Sparks, and relatives who were living on the Island of St. Croix, according to the book, “William Alexander Leidesdorff – First Black Millionaire, American Consul and California Pioneer.”

Folsom went to St. Croix to negotiate a price to purchase land located on the American River near the Sierra Nevada and close to a boom town where some Blacks became involved in gold

mining. On Nov. 3, 1849, The two parties settled that Leidesdorff’s family would receive $75,000 for the land. Sparks received the first installment of $5,000, but she refused the second amount of $35,000 when she learned that Folsom’s valuation of the land she owned was below the market rate. She filed a lawsuit against Folsom, but California law ruled in his favor.

By then, people in the area had already began calling a portion of the estate “Negro Bar,” an area on the American River where Black people were designated to live in tents and mining camps.

After the Black miners were forced to move, Folsom renamed the town Granite City. After his passing in 1855 at the age of 38, Granite City was renamed in Folsom’s honor. When Folsom took full control of Leidesdorff’s estate, the land’s value increased exponentially and made him a millionaire, according to Leidesdorff’s biography.

“Ms. Sparks was not well educated and could not read well,” said Shonna McDaniel, who operates the Sojourner Truth African Heritage Museum in Sacramento. “I believe he took an advantage of her, manipulating her into believing the land was worthless. It was just another way to take something of value in California.”

Both Allensworth and Negro Bar are California State Parks now.

Back in Los Angeles County, Hahn describes the arc of the Bruces’ story – from business savvy entrepreneurs for their time and resources to their sad fate — as an “American Dream that turned into a nightmare.”

The parcel the Bruce’s bought was dormant for almost 30 years before it was opened as a park in the 1960s. It was renamed Bruce’s Beach in 2007.

“This land was taken from the Bruce family because they were Black and, before it was stolen, was one of the precious few beaches Black families could enjoy,” Hahn said. “When I realized that the county now had ownership of the Bruce family’s original property, I felt there was nothing else to do but to give it back to its rightful owners.

Bruce’s Beach Park is currently housing L.A. County’s lifeguard training facility.

Last week, Bradford, who is chair of the California Legislative Black Caucus and an appointee to the state’s still-forming reparations task force, held a press conference to share details about SB 796.

“There comes a time when someone must take a position that is neither safe, nor political, nor proper,” said Bradford, quoting Martin Luther King, Jr. “He must take it because his conscience tells him it’s the right thing to do.”

He said the bill “would finally allow Bruce’s Beach to be returned to its rightful owners.”

L.A. County Board of Supervisor Holly J. Mitchell, L.A. County Fire Department Chief Daryl Osby, former Manhattan Beach Mayor Mitch Ward, Justice for Bruce’s Beach Founder Kavon

Ward, and Bruce family representative Duane Shephard, all attended the news conference, along with Bradford, Hahn and Muratsuchi.

“We’re not looking for an apology. We want our property back. We want restitution for the loss of revenue for 96 years from the generational wealth that would have been built up,” Shepherd said on MSNBC two days after the news conference. “We want punitive damages from the city of Manhattan Beach City Council and the police department at that time for colluding with the Ku Klux Klan to railroad our people out of there.”