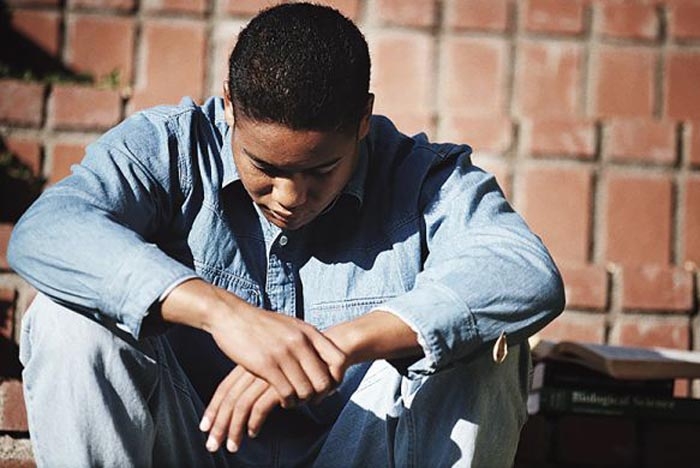

A16-year-old boy, a high school athlete with good grades, told his therapist that he was thinking about taking his own life. That therapist, Dennis Kolsch, got him admitted to an inpatient ward. “He didn’t have a great experience in there, but he was safe,” said Kolsch, a licensed mental health counselor in Cocoa Beach, Florida. “The family felt comforted knowing that.”

Teens leaving an inpatient program like this one will have discharge instructions on how to continue care, which usually includes medications and psychotherapy. The boy was discharged to Kolsch’s care, but Kolsch knew that weekly or biweekly therapy sessions were not enough. So he worked on getting the boy into an intensive outpatient program.

In the meantime, his parents were frantic. They didn’t want to let their son out of their sight, and felt they had to recreate the hyper-controlled structure of the hospital setting. It was all-consuming and exhausting. Further, the constant supervision was not helpful for the parent-child dynamic, which had been bumpy before the hospitalization and was now ramping up again. “The mom’s becoming overbearing and the son is withdrawing,” Kolsch said. “And then the mom gets worried because the son is withdrawing.”

Teens who have been hospitalized for a suicide attempt or suicidal ideation are at heightened risk of dying by suicide. A 2007 study, for instance, followed nearly 5,000 young people, from 15 to 24 years old, who sought care at a single hospital for “deliberate self-harm” over a 20-year period. Nearly 3 percent of study subjects died, and more than half of those deaths were likely suicide — a rate that was 10 times higher than would be predicted for this age group. And the increased risk, research shows, can persist for years.

“We know that transition out of inpatient care is a particularly high-risk time period for suicide and subsequent suicide attempts,” said Michele Berk, a clinical researcher at Stanford University.

For the full story, visit UnDark.org.