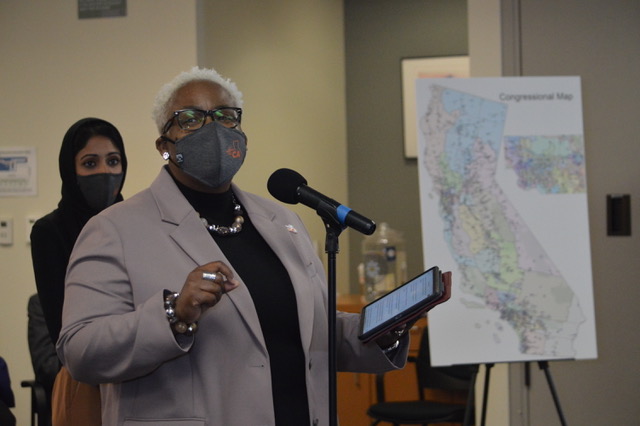

Redistricting Monitors Say Their Efforts Helped Protect the Black Vote

Antonio Ray Harvey | California Black Media

An advocacy group that fights for fair political representation of African Americans in California says it is pleased with the results of the state’s recent redistricting process.

Last year, the California Black Census and Redistricting Hub coalition, a.k.a. the Black Hub, led a grassroots initiative to ensure the state’s electoral map drawing process did not water down the voting power of African Americans across the state.

Last week, the California Citizens Redistricting Commission (CCRC) delivered finalized maps for the state’s U.S. Congress, State Senate, Assembly, and Board of Equalization voting districts to the Secretary of State’s office. The maps of the state’s electoral districts — updated once every decade to reflect the 2020 census count of population shifts and other demographic changes — will be used until 2031 to determine political representation in all statewide elections.

“All things considered, the (CCRC) had an arduous task. We commend their commitment to including Black voices in the redistricting process,” said James Woodson, policy director of the Black Hub.

Woodson said, in the Black Hub’s view, the CCRC did the best job possible within the rules of the “line-drawing process” to not disenfranchise “Black communities of interest.”

“Even in the areas where we didn’t get the perfect outcome, their attempts to consider the feedback of Black residents were fair. We are satisfied with the results,” Woodson continued.

Over the last three months, the CCRC drew four Board of Equalization districts, 52 Congressional districts, 40 Senatorial districts, and 80 Assembly districts.

During the process, the Black Hub coalition submitted draft maps to the commission based on community feedback they collected from hosting 51 listening sessions throughout California. The hub’s renderings, intended to guide the CRC’s decision-making process, reflected ideal boundaries

for greater equity in redistricting while simultaneously identifying opportunities to protect and increase Black political representation.

The Black Hub is a coalition of over 30 Black-led and Black-serving grassroots organizations focused on racial justice throughout California. Two years ago, the alliance organized another initiative to maximize the participation of Black Californians in the 2020 Census count.

CRCC Chair Isra Ahmad, who is employed as a Senior Research Evaluation Specialist with Santa Clara County’s Division of Equity and Social Justice, said the commission welcomed the feedback of people across the state.

“We drew district maps in an open and transparent manner that did more than merely allow public input — we actively sought and encouraged broad public participation in the process through a massive education and outreach program, afforded to us by the delay in receiving the census data,” she explained.

The CRCC is composed of five Democrats, five Republicans, and four Californians unaffiliated with either political party. They represent a variety of personal and professional backgrounds and come from different parts of the state.

During the map drawing process, the commission received letters and comments from a wide range of interested citizens, activists and advocacy organizations, all offering suggestions for how the CCRC should set geographic boundaries for districts. Often times, those requests offered opposing ideas.

“This was a very complicated process to understand and there were so many people who organized calls, developed social media campaigns and distributed information,” states Kellie Todd Griffin, Convening Founder of the California Black Women’s Collective, which launched a public awareness campaign to increase Black Californians participation in the CCRC public hearings. “Their actions helped ensure that the voices of our community were heard and valued when understanding our interest and our assets. It’s important that we keep this engagement active and continue to elevate the voice of California’s Black population.”

Last November, the California Hawaii State Conference of the NAACP informed the CCRC that it was “prepared to take legal action” if draft maps released to the public for comment last fall remained the way they were drafted.

Rick Callender, president of the California-Hawaii NAACP, said those iterations of the Assembly and Senate district maps for Los Angeles County and areas of the East Bay would have diluted Black political power. Los Angeles County and the East Bay are regions in the state where the highest numbers of Black Americans live.

During a news conference held before the commissioners delivered their final report to Secretary of State Shirley Weber’s office, the CCRC said it stood by its work and and took pride in the fact that the maps were drawn by hand.

CCRC commissioner Trena Turner (Democrat), a pastor and the Executive Director at Faith in the Valley, a multi-cultural, multi-faith community organizing network in the San Joaquin Central Valley, said the commission read as many public statements and news articles about redistricting as it could.

Turner said specific feedback like that heightened the commissions’ awareness.

“What that did, by writing the articles that they did, they served noticed. So, we were mindful that we were hearing their voices,” Turner told California Black Media (CBM). “‘let’s make sure we’re not breaking up historical areas’ to the best extent possible.’”

Redistricting commissioner Derric Taylor (Republican), a Black investigator with the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department and active volunteer, mentor, coach in the Los Angeles and San Gabriel Valley areas, told CBM that the only way to address Callendar’s and other interested parties’ concerns was by reading reports by the media.

If the concerns were not voiced in a public meeting, the commission had to adhere to the Bagley-Keene Open Meeting Act. California’s Bagley-Keene Open Meeting Act requires all state boards and commissions to publicly notice their meetings, prepare agendas, and accept public testimony in public unless specifically authorized to meet in closed session.

“The commission is bound by Bagley Keene,” Taylor said, adding that CCRC members could only discuss or address public comments “in a meeting or open forum to adhere to transparency.”

Because the federal government released the U.S. Census data the commission relies on to draw maps late, the CCRC made a request to the California Supreme Court to move their Dec. 15 deadline for final maps back by nearly a month, to Jan. 14. The state Supreme Court compromised and set the deadline for Dec. 27.

“I want to thank the Redistricting Commissioners for their hard work under challenging circumstances. We will now send these maps to the Legislature and to all 58 counties for implementation,” Secretary of State Weber responded after her office received the final maps.