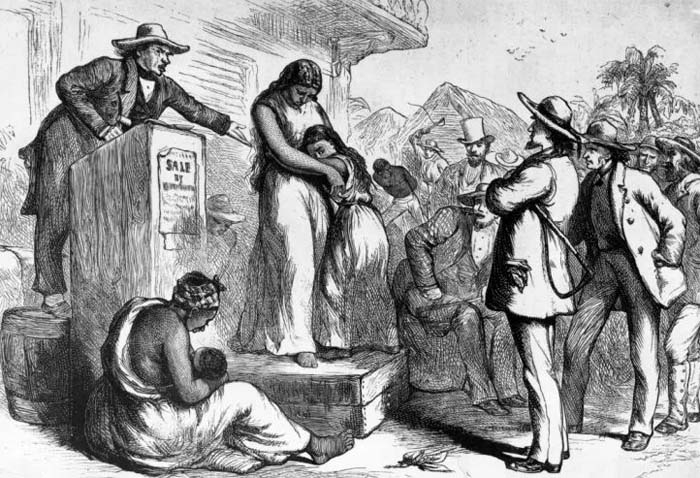

Americans are likely to think of New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day as a time to celebrate the fresh start that a new year represents, but there is also a troubling side to the holiday’s history. In the years before the Civil War, the first day of the new year was often a heartbreaking one for enslaved people in the United States.

In the African-American community, New Year’s Day used to be widely known as “Hiring Day” — or “Heartbreak Day,” as the African-American abolitionist journalist William Cooper Nell described it — because enslaved people spent New Year’s Eve waiting, wondering if their owners were going to rent them out to someone else, thus potentially splitting up their families. The renting out of slave labor was a relatively common practice in the antebellum South, and a profitable practice for white slave owners and hirers.

“‘Hiring Day’ was part of the larger economic cycle in which most debts were collected and settled on New Year’s Day,” says Alexis McCrossen, an expert on the history of New Year’s Eve and New Year’s Day and a professor of history at Southern Methodist University, who writes about Hiring Day in her forthcoming book Time’s Touchstone: The New Year in American Life.

But the history of New Year’s Day and American slavery is not all horror. The holiday was also associated with freedom.

The holiday became more associated with freedom than slavery when Abraham Lincoln signed the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing slaves in Confederate states on New Year’s Day in 1863. Slaves went to church to pray and sing on Dec. 31, 1862, and that’s why there are still New Year’s Eve prayer services at African-American churches nationwide. At such “Watch Night” services, congregants continue to pray for more widespread racial equality 157 years later.

For the full story, visit Time.com.